The study of palaeography is something which is one of the most enjoyable aspects of an archivist’s training, but it is not something which is the exclusive preserve of the professional. Anyone can learn to read old handwriting – all it takes is patience, determination, and lots of practice!

Handwriting styles

Over the centuries there have been several major styles of handwriting and handwriting from the medieval period to the 18th century will (generally speaking) fall into one of those styles, going from Anglicana (medieval period) to bastard Secretary (15th century) to Secretary (16th-17th cent) and italic (overlapping with Secretary) to mixed hands (late 17th cent – 19th cent). From 19th century onwards we’ve seen the rise of personal handwriting which doesn’t conform to a set, taught style, and ironically 20th and 21st century writing can be more difficult to read than Tudor, depending on the writer! In addition there are specialist hands used only in certain central law courts. A comprehensive survey of both handwriting styles and the tools used for writing from medieval times to the 18th century can be found at: http://scriptorium.english.cam.ac.uk/handwriting/history/

Abbreviations

Regardless of era there have also been well-established conventions for abbreviating words – think for example of ‘Mr’ for ‘Master’ or the ampersand & for ‘and’. These abbreviations need to be learnt off by heart if you are going to become confident at transcription.

See: http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/where_to_start.htm#abbreviations

Principles of palaeography

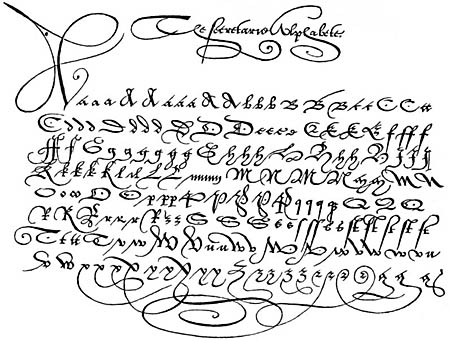

1. Familiarise yourself with the standard letter shapes for the particular style of writing in question – there is plenty of material available in the further reading section. Some hands look very similar to modern printed letter shapes – others look less familiar and will take time to learn, like learning the Russian or Greek alphabets. One of the most challenging is Secretary hand. It is a very good idea to run through a standardised Secretary alphabet before you get stuck into transcription:

2. The most important thing to remember is to compare the letter shapes within the same document. Remember that even though scribes are following a standard style, they have their own unique ‘take’ on it, and so you must use the individual document as the basis for your decisions, rather than just relying on the standard alphabets.

3. When starting out in reading documents try to take things letter by letter rather than guessing at whole words – you might be lucky and get some things right, but you could also be making lots of mistakes.

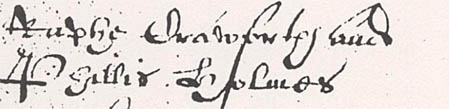

4. By recognising a letter in one word you can then apply that knowledge to the rest of the document. For example: in a Tudor marriage register you see this entry:

At first sight it looks a bit like gobbledegook but I can spot one word which I can definitely read – ‘and’. This gives me ‘a’, ‘n’ and ‘d’. I can see ‘a’ in the first and second names. So, a bit like a crossword puzzle, I have got part of those words. Now let’s look at the first word and see if there are any letters which are easy to get – ‘p’ looks straightforward in the middle. So I’ve got ‘*ap**’

The fourth letter looks like the second letter of the name immediately below – I think this might be ‘Phillis’ so let’s say it’s ‘h’. I’ve now got ‘*aph*’

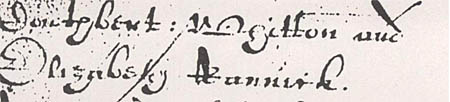

Looking at the final letter I can’t see anything identical in this small part of the register, so I need to look at other words by the same scribe to see if I can see it again. Looking further down the same page I find

The female name here is easy – ‘Elizabeth’ – so I can now see that the last letter of the first word is ‘e’. So I’ve now got ‘*aphe’

The initial letter may still be unfamiliar but it also appears at the beginning of Elizabeth’s surname. It is in fact a capital ‘R’ – in Secretary hand this has a single foot rather than the two we’re used to today. So the first name is ‘Raphe’.

Now see if you can get Raphe’s surname by comparing letter shapes. If you want to check your reading see the answers at the bottom of the page.

5. Spelling in the past was phonetical rather than following the rules we are used to today. Therefore the same word can be spelt in many different ways, even within the one document, even as late as the 19th century. This can lead to confusion and false assumptions, particularly in relation to family history and the spelling of surnames. If in doubt, try and say the word out loud, preferably with the accent of the writer.

6. Beware the minims which can all look the same – these are the small strokes which are used to make up the letters “i”; “m”; “n”; “u” and “v”. Use common sense as to which might be being used depending on the sense of the word – eg there is no word ‘receyne’ but there is a word ‘receyve’

7. If you are having difficulty reading and transcribing a particular word, there are two ways of tackling it. Firstly, try and divide down the word into its individual letter forms and transcribe them individually – it sometimes helps if you block out all the other letters so that you can only see one letter at a time. Alternatively, if this does not work, leave a space for the word and continue the transcription. Come back to it at the end to see if you can then decipher it having read and hopefully understood the rest of the document. If neither of these two methods work, do not look at the document for a couple of hours and then go back to it with a clear mind and without any preconceptions of what it should say.

Claire Skinner, Principal Archivist

Further reading:

There is a lot of material on-line to help you learn how to read old handwriting. Two of the best are:

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/palaeography/default.htm

and http://paleo.anglo-norman.org/empfram.html (the latter deals with the early modern period.)

You can also learn palaeography through courses at your local archive service or you may even like to take part in a distance learning course such as those run by the University of Dundee – http://www.dundee.ac.uk/cais/teaching.htm – or Strathclyde.

There are also some excellent books: L. C. Hector: ‘The Handwriting of English Documents’ is a classic work, but is now out of print; Hilary Marshall: ‘Palaeography for Family and Local Historians’ is very accessible, and still in print. Last but by no means least, I recommend ‘Reading Tudor and Stuart Handwriting’ by my colleague Steve Hobbs, together with Lionel Munby and Alan Crosby.

Answers to marriage register entries

Raphe Crawforth and

Phillis Holmes

Couthbert Whitton and

Elizabeth Rannick