国际知名历史学者John E. Wills, Jr. (1936-2017,卫思韩)于2017年1月13日不幸过世。卫教授曾任教于南加州大学,师承“中国通”费正清(John King Fairbank)先生。他通中、日、荷、德、法、葡、西等多种语言,研究领域含括海洋史、海洋史、交流史、全球史等,尤以明清史、荷兰、葡萄牙殖民史著称。

John E. Wills, Jr., a longtime leader of China studies at USC and the Chinese history field, passed away on January 13. He was 80 and had been in poor health. Jack, as he was known by his friends and colleagues, began teaching at USC in 1965 and retired in 2004. Many, however, would never have guessed that he formally retired. Relentlessly curious, Wills remained a campus fixture. He continued mentoring students, organizing conferences, and writing books and articles.

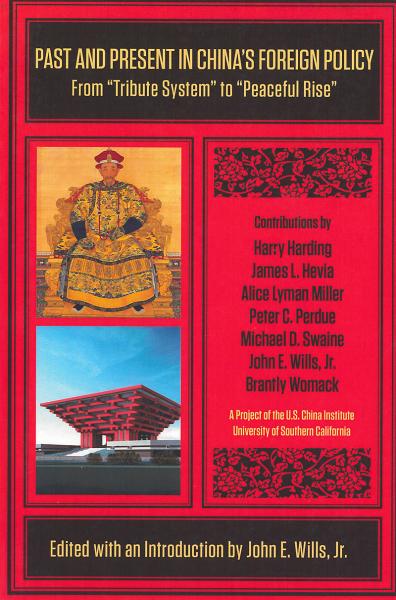

When the USC U.S.-China Institute was launched in 2006, Wills was there full of ideas and eager to be a part of things. He received one of the institute’s first research grants and put together a workshop of other distinguished historians, political scientists, and policy analysts. They focused on how the history of China’s foreign relations could help those working to understand Chinese foreign policy today. That project yielded first, a special issue of The Journal of American-East Asian Relations and then the book Past and Present in China’s Foreign Policy: From “Tribute System” to “Peaceful Rise” (2010). Following that, Wills worked with other campus units to organize gatherings focused on the role of print in the making of the modern world. That work built on his ongoing interest in Chinese travel writing and on the impact 17th century European books had on European consciousness of a wider world.

When the USC U.S.-China Institute was launched in 2006, Wills was there full of ideas and eager to be a part of things. He received one of the institute’s first research grants and put together a workshop of other distinguished historians, political scientists, and policy analysts. They focused on how the history of China’s foreign relations could help those working to understand Chinese foreign policy today. That project yielded first, a special issue of The Journal of American-East Asian Relations and then the book Past and Present in China’s Foreign Policy: From “Tribute System” to “Peaceful Rise” (2010). Following that, Wills worked with other campus units to organize gatherings focused on the role of print in the making of the modern world. That work built on his ongoing interest in Chinese travel writing and on the impact 17th century European books had on European consciousness of a wider world.

Wills was always in a hurry and eager to learn. He finished high school a year early and graduated in 1956 from the University of Illinois with high honors a year early. He went into the army and it was in the library at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio where he found and read a copy of Edgar Snow’s Red Star over China. After leaving the army, Wills went briefly to the University of Chicago before heading to Harvard where he would earn his masters and doctorate.

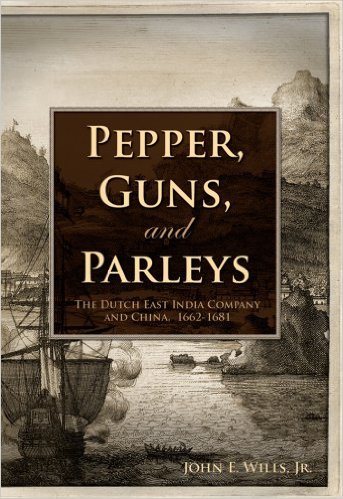

Carolin “Connie” Wills, Jack’s wife of 58 years, said that while it was the story of China’s Communist revolution that first caught her husband’s attention that “he just kept going back and back into China’s history.” At Harvard, Wills began exploring China’s early contact with Europeans, a task that would require him to learn numerous languages and dive deep into the archives of the Dutch East India Company. His first book, Pepper, Guns, and Parleys: The Dutch East India Company and China, 1662-1681, published in 1974, grew out of the research he began as a graduate student. (The company’s Fort Zeelandia in Taiwan is pictured above.) In the Journal of Asian Studies, Robert Gardella highlighted Wills’s painstaking research which brought imperial and company concerns and the lives and tactics of traders to light: “Official Chinese sources ritually emphasized tribute missions to Peking and tended to ignore such rustic matters as coastal trade and provincial diplomacy.” From this first book, Wills was exploring “the problems of inter-cultural communication.”

Carolin “Connie” Wills, Jack’s wife of 58 years, said that while it was the story of China’s Communist revolution that first caught her husband’s attention that “he just kept going back and back into China’s history.” At Harvard, Wills began exploring China’s early contact with Europeans, a task that would require him to learn numerous languages and dive deep into the archives of the Dutch East India Company. His first book, Pepper, Guns, and Parleys: The Dutch East India Company and China, 1662-1681, published in 1974, grew out of the research he began as a graduate student. (The company’s Fort Zeelandia in Taiwan is pictured above.) In the Journal of Asian Studies, Robert Gardella highlighted Wills’s painstaking research which brought imperial and company concerns and the lives and tactics of traders to light: “Official Chinese sources ritually emphasized tribute missions to Peking and tended to ignore such rustic matters as coastal trade and provincial diplomacy.” From this first book, Wills was exploring “the problems of inter-cultural communication.”

By this time, Wills was already teaching at USC and working with others such as Theodore Hsi-en Chen, Wen-hui Chen and George Totten to build Asian studies at USC. In talking about Prof. Wills, his longtime friends and colleagues Professors Thomas Gustafson (English) and Stanley Rosen (Political Science) highlighted his love of the university. They noted that just as he was a meticulous researcher, he was a stickler for details while on committees. Among committees he chaired were ones to determine coursework students should take to qualify as secondary school social studies teachers. He also served on committees to shape general education where he pushed to require students to study Asian civilizations as well as Western civilization. He chaired the East Asian Languages and Cultures Department from 1987 to 1989 and he served as director of the East Asian Studies Center in 1990-91 and from 1992 to 1994.

All the while, Wills continued to research and publish path-breaking work. This included contributions to The Cambridge History of China (From Ming to Ch’ing: Conquest, Region and Continuity in Seventh-Century China (co-edited with Jonathan Spence, 1979) , and Embassies and Illusions: Dutch and Portuguese Envoys to K’ang-hsi (1984). In 1980, he launched a new course, Chinese Lives, which aimed to explore Chinese history through biographies. His work on this eventually yielded Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History. When it first came out in 1995, Wills told Trojan Family Magazine, “[t]his reflects a very Chinese approach or mentality, because of the emphasis on biographies. This is really a book about Chinese memory.” Covering Chinese history from legendary and historical figures from 2000 BCE through the Deng Xiaoping initiated economic reforms and the 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen Square and elsewhere, Wills’s book became a favorite. In his Journal of Asian Studies review of it, Jerry Dennerline concluded, “This is not a romance, it is Chinese history. Every historian masquerading as a teacher should read it.” Wills updated the book in 2012, and of that edition Aaron Pickering insisted in Education about Asia, “Mountain of Fame should be on the reading list of anyone tasked with teaching a survey of Chinese or world history.”

All the while, Wills continued to research and publish path-breaking work. This included contributions to The Cambridge History of China (From Ming to Ch’ing: Conquest, Region and Continuity in Seventh-Century China (co-edited with Jonathan Spence, 1979) , and Embassies and Illusions: Dutch and Portuguese Envoys to K’ang-hsi (1984). In 1980, he launched a new course, Chinese Lives, which aimed to explore Chinese history through biographies. His work on this eventually yielded Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History. When it first came out in 1995, Wills told Trojan Family Magazine, “[t]his reflects a very Chinese approach or mentality, because of the emphasis on biographies. This is really a book about Chinese memory.” Covering Chinese history from legendary and historical figures from 2000 BCE through the Deng Xiaoping initiated economic reforms and the 1989 demonstrations in Tiananmen Square and elsewhere, Wills’s book became a favorite. In his Journal of Asian Studies review of it, Jerry Dennerline concluded, “This is not a romance, it is Chinese history. Every historian masquerading as a teacher should read it.” Wills updated the book in 2012, and of that edition Aaron Pickering insisted in Education about Asia, “Mountain of Fame should be on the reading list of anyone tasked with teaching a survey of Chinese or world history.”

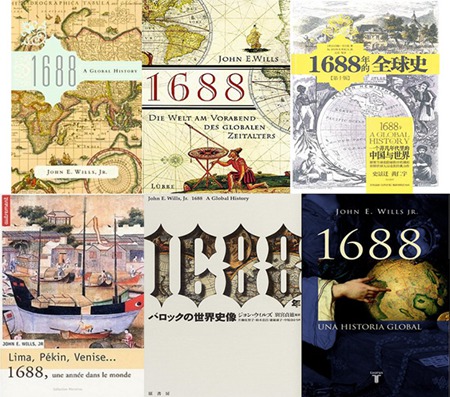

Charlotte Furth, Wills’s long time friend and colleague, highlighted the scholar’s wide-ranging interests and how that helped him produce yet another seminal survey. She notes, “Jack was one of a kind—he knew something about almost everything. He travelled almost everywhere. He could talk about almost any subject, nonstop. While China and Chinese history was his first love, when in the 1990s, historians had to face the challenge of teaching and researching world history, everyone turned to Jack and he delivered.”

Furth is referring to Wills’s 1688: A Global History which came out in 2001. The book became a Los Angeles Times bestseller and was soon translated into several languages. The English version was short-listed for a British PEN prize and the German version was named by the history magazine Damals as the best history book in 2002. Some of the editions of the book are pictured below (U.S., German, Chinese, French, Japanese, and Spanish).

Many would be content to rest on such laurels, but Wills continued his research editing and contributing to Eclispsed Entrepots of the Western Pacific: Taiwan and Central Vietnam, 1500-1800 (2002) and China and Maritime Europe, 1500-1800 (2011). He also published two dozen additional articles and another history survey, The World from 1450 to 1700 (part of The New Oxford World History, 2009). His vorcious reading and writing never stopped. He published “What’s New? Studies of Revolution and Divergence, 1770-1840” in the Journal of World History in 2014 drawing on forty-four books in his sixty-page state of the field essay.

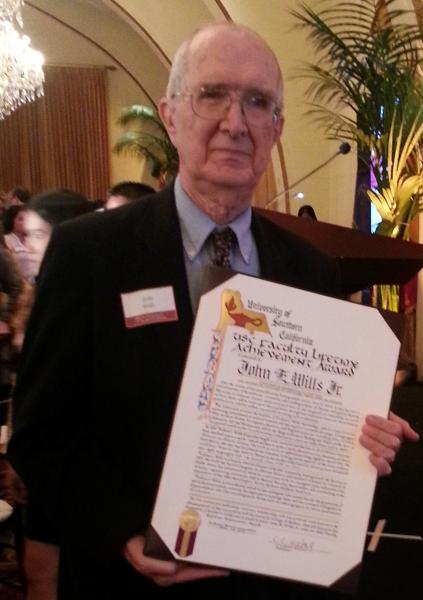

In 2013, USC celebrated Wills’s commitment and many accomplishments with its Faculty Lifetime Achievement Award. USC President C.L. Nikias noted, “Few historians possess the breadth of Professor Wills’ knowledge, which comes from his unstinting commitment to archival research and his superior command of a range of languages… His work in Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and English archives, including those in India, Indonesia and the Philippines, and in the Qing archives in Beijing and Taipei, made him a recognized world leader in scholarship on European relations with China before 1800.”

In 2013, USC celebrated Wills’s commitment and many accomplishments with its Faculty Lifetime Achievement Award. USC President C.L. Nikias noted, “Few historians possess the breadth of Professor Wills’ knowledge, which comes from his unstinting commitment to archival research and his superior command of a range of languages… His work in Dutch, Portuguese, Spanish and English archives, including those in India, Indonesia and the Philippines, and in the Qing archives in Beijing and Taipei, made him a recognized world leader in scholarship on European relations with China before 1800.”

Jack Wills was a mentor to many and celebrated mentorship. One undergrad who came along after Wills had retired was Christopher Alesevich. Inspired by Wills’s use of biography, Alesevich interviewed Wills and others about John King Fairbank, Wills’s adviser at Harvard and a pioneer in American China studies. Alesevich’s US-China Today article quoted Wills on how Fairbank worked to foster interaction among scholars, including ones who might otherwise be loners.

In 2006, to further facilitate mentorship, Prof. Wills donated $50,000 to establish a fund at the USC East Asian Studies Center for graduate students to assist faculty in research, learning as they worked. He told USC News, “By watching an established, high-functioning researcher do his or her work and participating in that work, the student learns a great deal about how to become a researcher.” Wills was especially eager to support foreign students who were not eligible for the Foreign Language and Area Studies awards provided to USC and other schools by the U.S. government.

Typical of Wills, the gift was made anonymously. Stanley Rosen, then EASC director, pushed Wills to allow the center to acknowledge him, arguing that his example would encourage others to support such work. Ever loyal to the program he’d done so much to build, Wills relented and let it be known that he had made the donation. Wills also participated in USCI’s program to help teachers bring Asia alive for their students.

Wills’s generosity with his time was something Cathy and his other four children highlighted. He and his wife, Connie, were members of the League of Women Voters. He worked as an election volunteer and in February 2008 he brought a contingent of forty Beijing middle school school students to a polling place at the Armenian Brotherhood Bible Church in Pasadena. The San Gabriel Valley Tribune interviewed the students and their teacher Liu Yang, who noted how interesting it was to see a process they’d only read about.

That visit to the polls came about because Wills was also an active member of the Pasadena Sister City Association, which had hosted the visit from its Chinese partner, Beijing’s west district. Wills firmly believed that such civic organizations and direct people to people contacts were essential to deepenly cross-cultural understanding. Wills was an inveterate traveller. Among the trips he made was one with the Sister City group to China, attending the 2010 Shanghai World Expo. Of course, Wills’s own research demonstrated the role played by merchants, missionaries and many others in international affairs.

That visit to the polls came about because Wills was also an active member of the Pasadena Sister City Association, which had hosted the visit from its Chinese partner, Beijing’s west district. Wills firmly believed that such civic organizations and direct people to people contacts were essential to deepenly cross-cultural understanding. Wills was an inveterate traveller. Among the trips he made was one with the Sister City group to China, attending the 2010 Shanghai World Expo. Of course, Wills’s own research demonstrated the role played by merchants, missionaries and many others in international affairs.

Jack Wills’s scholarship and his example of civic engagement has inspired many. Some of his students celebrated him at a symposium in March 2015 and plan to publish the papers presented then in his honor. In addition to scholars and students, some of his close friends from the Neighborhood Unitarian Universalist Church attended. He is survived by his wife, five children and their spouses, seven grandchildren, and four great-grandchildren.

******

Jan. 28, 2017 update

From R. Bin Wong, UCLA: “Jack Wills was a great senior colleague who was part of the generation who pioneered the integration of Chinese history into broader regional and global historical scholarship. He once quipped that while he was a graduate student at Harvard (now more than a half century ago) he and the late Joseph Fletcher would say if it came by land to China it was Fletcher’s and if by sea it was Wills’s—what I now think of as a clarion, not unlike Paul Revere’s, about the historiographical revolution that was to come, in part because of what Jack Wills accomplished.”

Jan.30, 2017 update

From Paul Van Dyke, one of Wills’s students, Sun Yatsen University: “Jack Wills has been an inspiration to all of us, always willing to help students and scholars whenever the opportunity arose, and a source of incredible knowledge and wisdom. Even when I thought I had covered a topic as thoroughly as humanly possible, Jack had another book to examine and a new angle to consider. When the research ran in circles with no end, Jack opened a door and showed me a way out. He was a true mentor, bar none, and I know I am not alone when I say, we will miss you Jack!”